Fact-check: An experienced MD researcher made dubious claims about a supplement for multiple sclerosis

Short on time? Read the summary:

→ Terry Wahls, MD, MBA is the author of three books that have been (and still are) bestsellers. Her books occupy a substantial amount of consumer space online. If someone has MS, autoimmunity, or chronic disease and they search for nutrition or diet on Amazon or Google, they're almost certain to come across a Wahls book.

→ This article isn't a review of Wahls' books. It only considered one specific social media post. But it does illustrate some common problems in the health and nutrition market, including trust without responsibility.

→ People trust advice that comes from Wahls and others who have medical credentials and large platforms. This isn't a referendum on everything Wahls has written or said, but the particular supplement claims made in the social media post are decidedly misleading. People have bought this supplement as a direct result of her promotion, yet there's no recourse if or when they find that it has no effect or causes harm.

→ Vague wording that implies stronger evidence than exists is particularly misleading for people who do not have medical or scientific backgrounds. It could be construed as using an educational advantage for profit.

→ Inflated claims are common in marketing. But when it comes to products or programs that have been created for a specific purpose like treating a disease or supporting wellness, there should be stronger ethical protections in place to help consumers know when something is proven versus something that is experimental because there's not enough data to know how it affects humans. Humans aren't mice, rats, or cells confined to a test tube.

→ Modified citrus pectin has been marketed by Wahls and recommended to an audience that primarily has MS or other autoimmune-related concerns. But there's no human studies that have analyzed this compound in people with these conditions.

→ It's concerning to see an MD with a very large platform promote a supplement that isn't only experimental, but barely studied in humans at all. People born with prostates are not interchangeable with people born with uteruses. Yet persons born female are the ones predominantly affected by MS and autoimmune disease.3 There are multiple concerns that this supplement is being broadly recommended to an audience in which it has not been studied.

Terry Wahls, an MD with an MBA, is a researcher at the University of Iowa.1 Alongside her research team, Wahls has published several scholarly articles on multiple sclerosis diet and lifestyle programs, most of which relate to the protocols that she has designed.2 She also writes non-scholarly books aimed at people with MS, chronic illness, and autoimmunity.

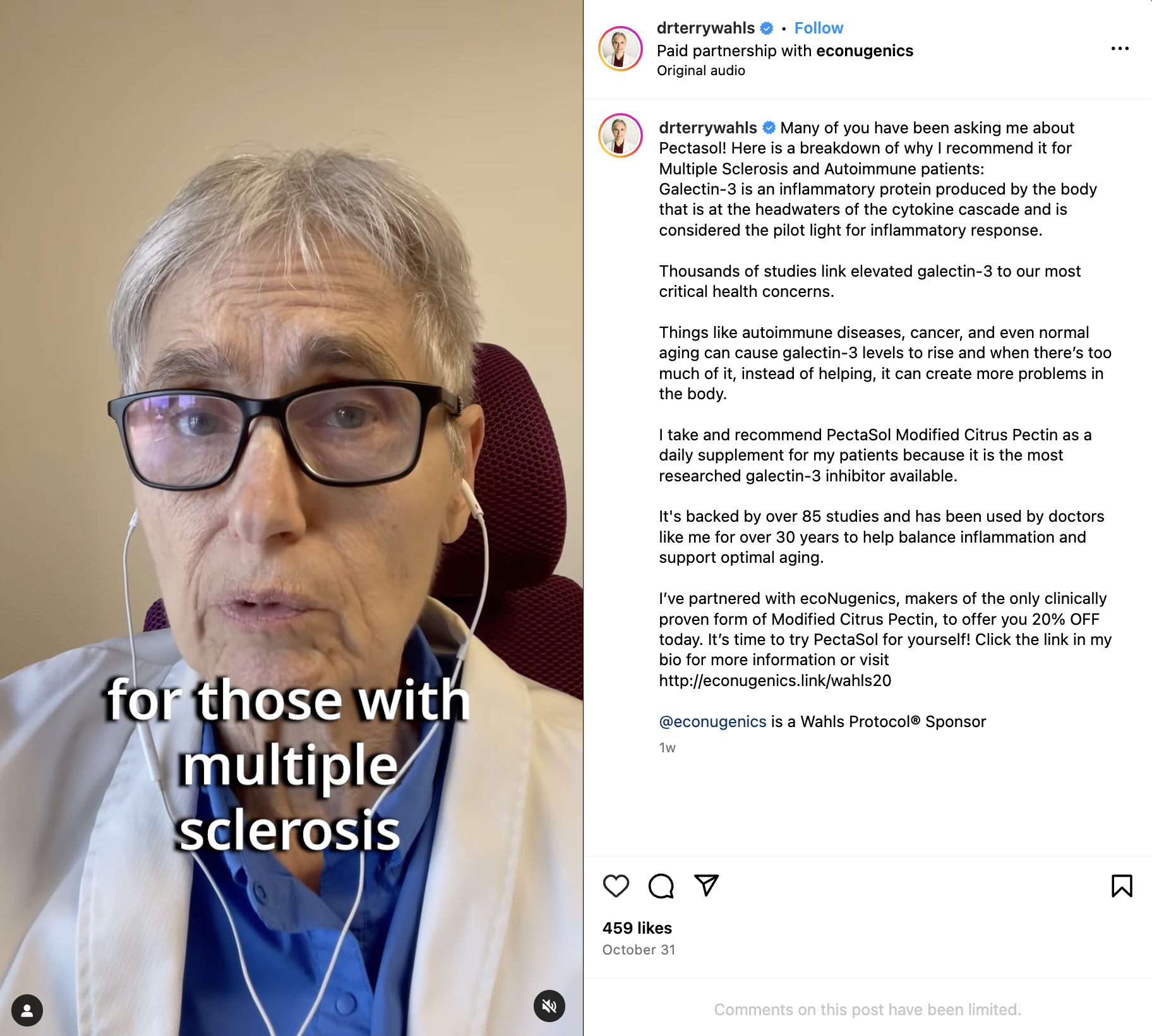

Last week, Wahls shared a video on her Instagram account promoting Pectasol, a modified citrus pectin supplement.

If you have multiple sclerosis, autoimmune disease, chronic illness, or have concerns about brain health and Alzheimer's prevention, you may see her video and be tempted to buy this supplement. Based on her claims, it sounds like a simple, effective remedy.

It isn't. And I will explain, line by line, why these claims can't be verified.

Fact-checking Wahls' claims about citrus pectin

Claim 1: "Many of you have been asking me about Pectasol."

- You might think this doesn't sound like a claim, but this implies interest and popularity.

- This is a common marketing technique for wellness and sales in general. Hyping the idea that a product is in high demand is marketing 101. It also helps to drop barriers, like critical thinking, about the product.

Fact: There's no way to confirm whether this is true. However, interest from others can't be used to prove the validity of a product or how well it works, so claims like this should be viewed with more skepticism than not.

Claim 2: "Thousands of studies link elevated galectin-3 to our most critical health concerns."

- Her post says, "Here is a breakdown of why I recommend it for multiple sclerosis and autoimmune patients," and explains that galectin-3, a protein, is linked with inflammation and cytokine cascades. She calls galectin-3 the "pilot light for the inflammatory response."

- She says that autoimmune disease, cancer, and normal aging increase this galectin-3 protein, and too much of it creates problems in the body.

- This article doesn't fact-check what galectin-3 does or how it works. Instead, it's focused on the claim that thousands of studies link elevated levels of this protein to human health concerns. Thousands is a lot of studies.

The fact-check, step-by-step:

- I go to PubMed, the database used by medical and health researchers. I enter the search term "galectin-3" with no filters. Result: 5,937 studies

- I refine the results, filtering for only results that include "humans." Result: 4,032 studies

- But these 4,000+ studies include many article types, including reviews that don't present original research. They may discuss other studies, theories, or concepts that relate to humans but only present data from animal or cell studies. These won't help us determine if this protein has been linked to humans with original research. So, I add the filter "randomized controlled trial" because this type of study is designed to tell us something specific in humans. Result: 70 studies

- That's not thousands of studies. I expand the search filter to include clinical trials, which are often not designed to help draw explicit conclusions about human health. But to thoroughly vet the claim, I'll see if there are many more of these. Result: 121 studies

- While the claim doesn't specifically say "our most critical health concerns in humans," that is the implication. Her audience is likely a mix of practitioners and patients, but she's directing this post to people with MS and autoimmune conditions. When a patient who hasn't been trained in scientific research reads this claim, they will likely assume that these thousands of studies refer to information directly relevant to humans.

Fact: This claim is misleading. If the implication refers to studies done in humans, it is demonstrably false.

Claim 3: "I take and recommend Pectasol modified citrus pectin as a daily supplement for my patients because it is the most researched galectin-3 inhibitor available."

- There's no way to verify that she takes this supplement. Claims like this can be powerful since she has MS, which can lend undeserved credibility to a supplement's effectiveness.

- There's no way to verify if she recommends it to her patients or if she is currently in active clinical practice. According to her website, she appears to work mostly with clinical research and running her brand.

- As for being the "most researched galectin-3 inhibitor available," let's go to PubMed.

The fact-check, step-by-step:

- At PubMed, I enter the search term "galectin-3 inhibitor." This time, I'm leaving the filters in place for humans, randomized controlled trials, and clinical trials. Result: 35 studies

- But now I need to know if these results say that modified citrus pectin is one of them and is the "most researched." I refine the search term to "galectin-3 inhibitor citrus pectin." Result: 1 study

- Another galectin-3 inhibitor, a pharmaceutical compound, had several studies.

Fact: This claim is false. Based on finding more studies on other galectin-3 inhibitors in humans, citrus pectin is not the most-researched inhibitor.

Caveat: If the claim is that it's the most researched one available, and the entire claim hinges on that one word (and, in this case, it may), then the statement is still misleading. Just because a product can be purchased over-the-counter as a supplement and that it's the only substance of its kind does not mean that it works for these purposes or has been proven safe or effective.

Claim 4: "It's [modified citrus pectin] backed by over 85 studies and has been used by doctors like me for over 30 years to help balance inflammation and support optimal aging."

- The first part, "backed by over 85 studies," will be easy to check.

- It's not possible to verify whether doctors like her have been using it or what that means. But since this can't be verified, it's also not possible to confirm that it's true. Relatedly, just because a medical provider recommends a supplement does not mean it has been proven to work in humans.

The fact-check, step-by-step:

- At PubMed, I enter the search term "modified citrus pectin." I still have results filtered to include human studies and randomized controlled or clinical trials. Result: 3 studies

- The three studies all involve prostate cancer. So, this supplement has not been studied in humans to look for effects on multiple sclerosis or autoimmune disease—the things that were specifically referenced in the Instagram post.

- This number is also, of course, not 85 studies. So it's clear that "backed by" doesn't mean studies in humans. For curiosity and to figure out where the 85 number came from, I remove the filters for the randomized controlled trial. Result: 3 studies

- Next, I remove the filter for clinical trials. Result: 73 studies

- That's closer to 85, but still, ultimately, this supplement seems to be mainly backed by cell and animal studies. These are not useless in science, but they do not help decide how a supplement affects a human.

Fact: This claim is misleading because it signals implied trust that non-researchers will likely assume means that 85 studies tell how it works in humans. There only appears to be human data for prostate cancer from three studies.

Claim 5: Paid partnership with econugenics

- While this fact isn't exactly a claim, it's one of the most vital parts of this post. This is an ad.

- In the post, Wahls provided access to 20% off by providing an affiliate link, which means that she gains some profit or other benefit from each purchase made through that link.

- Econugenics, the brand that makes the supplement, is a sponsor of Wahls' programs. So they have a two-way financial relationship.

Fact: Financial relationships are conflicts of interest. This does not necessarily mean that what was said is false (although the claims can hardly be said to be proven). But claims made should be interpreted through the lens that she benefits from each sale. In general wellness marketing, this could mean potentially inflating benefits while neglecting to mention how little is known or downplaying potential concerns from an unbiased research perspective.

False claims? Bad results? No responsibility

Most influencers, experts, and online businesses use legal disclaimers. They're meant to protect companies from accidental omissions of information that may lead to harm or the use of content for reasons other than the company's intended purpose. For example, most will state that they provide education only, not medical advice.

With disclaimers and legal policies in place, businesses can feel more confident in the claims their content makes. They're not bound by codes of ethics to verify or warrant that all content is true based on scientific consensus or peer review.

Basically, as with any other business, health-related and wellness companies can largely say whatever they want. Supplement companies are supposedly more limited by FDA and FTC regulations. They have to include the following disclaimer on their products and their websites. It's usually found at the bottom of the website footer, in the tiniest font possible. It reads:

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. These products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

Wahls doesn't have a disclaimer in the footer of her website. Instead, it's located in the Terms & Conditions section, where all liability for any potential harm or outcome is placed entirely on the consumer. While this is fairly typical for any website's terms and conditions, it isn't front and center or easily found by those who visit her website for diet, health, or supplement information. Patients/consumers may be unaware that, legally, she's not responsible for anything she writes, says, sells, or does.

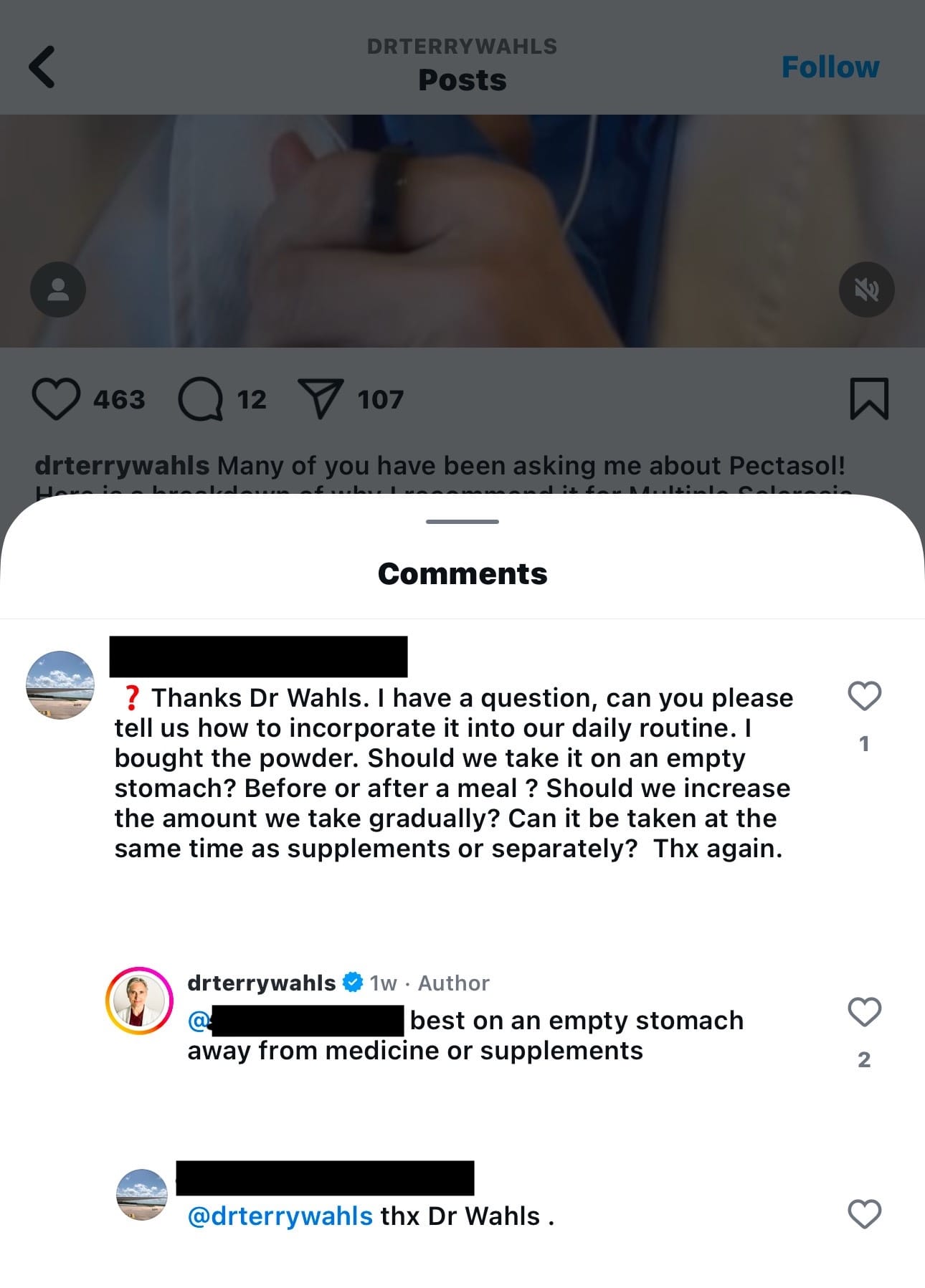

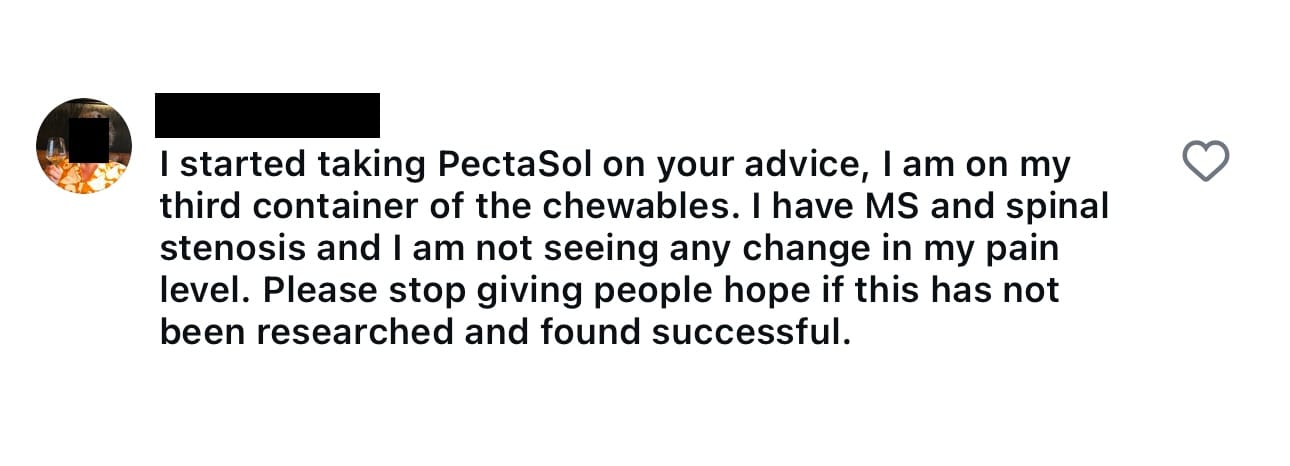

There is also no reference to a disclaimer in her Instagram bio. Patients or consumers who interact with her in the comments there may not be explicitly aware that she isn't providing medical advice, because it looks an awful lot like she's advising:

If this, then what?

If Wahls endorses this supplement with an extreme lack of human data, it raises countless questions about the other claims that she makes in her books.

She is a published researcher, professor, and medical provider who is well-versed in the scholarly space. She has the skill set to vet and validate research. That makes her use of ambiguous verbiage like "thousands of studies" and "backed by over 85 studies" concerning.

In all likelihood, the wording was provided by the marketing department of the supplement company. Regardless, she chose to use first-person language in her post on her personal social media account. She also sent the promotion via her email list.

Screenshot from 11/8/2024 of an email sent by Terry Wahls on 10/31/2024 with the subject "Nothing Worked Until PectaSol"

When medical providers or people with advanced credentials use their expertise and platform to promote supplements for profit, it raises concerns. When a promoted product appears to be substantially misrepresented, that leads to significant questions from researchers and journalists, but should also concern consumers.

Medical doctors know cell and animal studies should not be used to inform clinical practice guidelines. At the very least, the use of this supplement is experimental. But consumers might be less excited to try an experimental product that has never been studied in patients with MS.

Request for comment

The social media post reviewed in this article has comments limited. If Wahls or her team responds to requests for comment, this article will be updated.

Summary

- Terry Wahls, MD, MBA is the author of three books that have been (and still are) bestsellers. Her books occupy a substantial amount of consumer space online. If someone has MS, autoimmunity, or chronic disease and they search for nutrition or diet on Amazon or Google, they're almost certain to come across a Wahls book.

- This article isn't a review of Wahls' books. It only considered one specific social media post. But it does illustrate some common problems in the health and nutrition market, including trust without responsibility.

- People trust advice that comes from Wahls and others who have medical credentials and large platforms. This isn't a referendum on everything Wahls has written or said, but the particular supplement claims made in the social media post are decidedly misleading. People have bought this supplement as a direct result of her promotion, yet there's no recourse if or when they find that it has no effect or causes harm.

- Vague wording that implies stronger evidence than exists is particularly misleading for people who do not have medical or scientific backgrounds. It could be construed as using an educational advantage for profit.

- Inflated claims are common in marketing. But when it comes to products or programs that have been created for a specific purpose like treating a disease or supporting wellness, there should be stronger ethical protections in place to help consumers know when something is proven versus something that is experimental because there's not enough data to know how it affects humans. Humans aren't mice, rats, or cells confined to a test tube.

- Modified citrus pectin has been marketed by Wahls and recommended to an audience that primarily has MS or other autoimmune-related concerns. But there's no human studies that have analyzed this compound in people with these conditions.

- It's concerning to see an MD with a very large platform promote a supplement that isn't only experimental, but barely studied in humans at all. People born with prostates are not interchangeable with people born with uteruses. Yet persons born female are the ones predominantly affected by MS and autoimmune disease.3 There are multiple concerns that this supplement is being broadly recommended to an audience in which it has not been studied.

References