Can ultra-processed foods be healthy?

Ultra-processed foods have been increasingly highlighted as a tension point among those who work in nutrition, health, or wellness.

Ultra-Processed Upset

A Time article from August described the efforts of Jessica Wilson, a registered dietitian fighting for ultraprocessed foods—and it's not because she works for the food industry.

How did it come to this? Last summer, Chris van Tulleken's book Ultra-Processed People was released, leading to a media hype-fest about ultra-processed foods. Wilson noted that panic over these foods was more about race, class, and access than the ingredients themselves.

So, she decided to do her own experiment. She got over 80% of her calories from ultra-processed foods for a month. The Time article described her typical diet during this phase:1

"She swapped her morning eggs for soy chorizo and replaced her thrown-together lunches...with Trader Joe’s ready-to-eat tamales. She snacked on cashew-milk yogurt with jam. For dinner she’d have...Costco pupusas, or maybe chicken sausage with veggies and Tater-Tots."

How did Wilson feel after the month? She had more energy and motivation, coupled with less anxiety. It's not because she ate "junk"—a misapplied label given to some ultra-processed foods. She felt it was because of eating complete meals during this time compared to "haphazard combinations of whole-food ingredients."

But, her experiment and the Time article raised ire in the nutrition and wellness world. Big names in the field took to social media and various publications to issue warnings and criticize the idea that ultra-processed foods are acceptable.

Mark Hyman, MD, one of the biggest names in functional medicine, whose books include Ultra-Prevention, Ultra-Metabolism, and Young Forever, had plenty to say about the Time article. In response, he posted an Instagram reel, saying that it "downplayed the dangers of ultra-processed food."

He said, "There's literally hundreds and hundreds of extensive research (studies) linking ultra-processed food to all kinds of serious health risks..."

Fact-check: Hundreds and hundreds of studies?

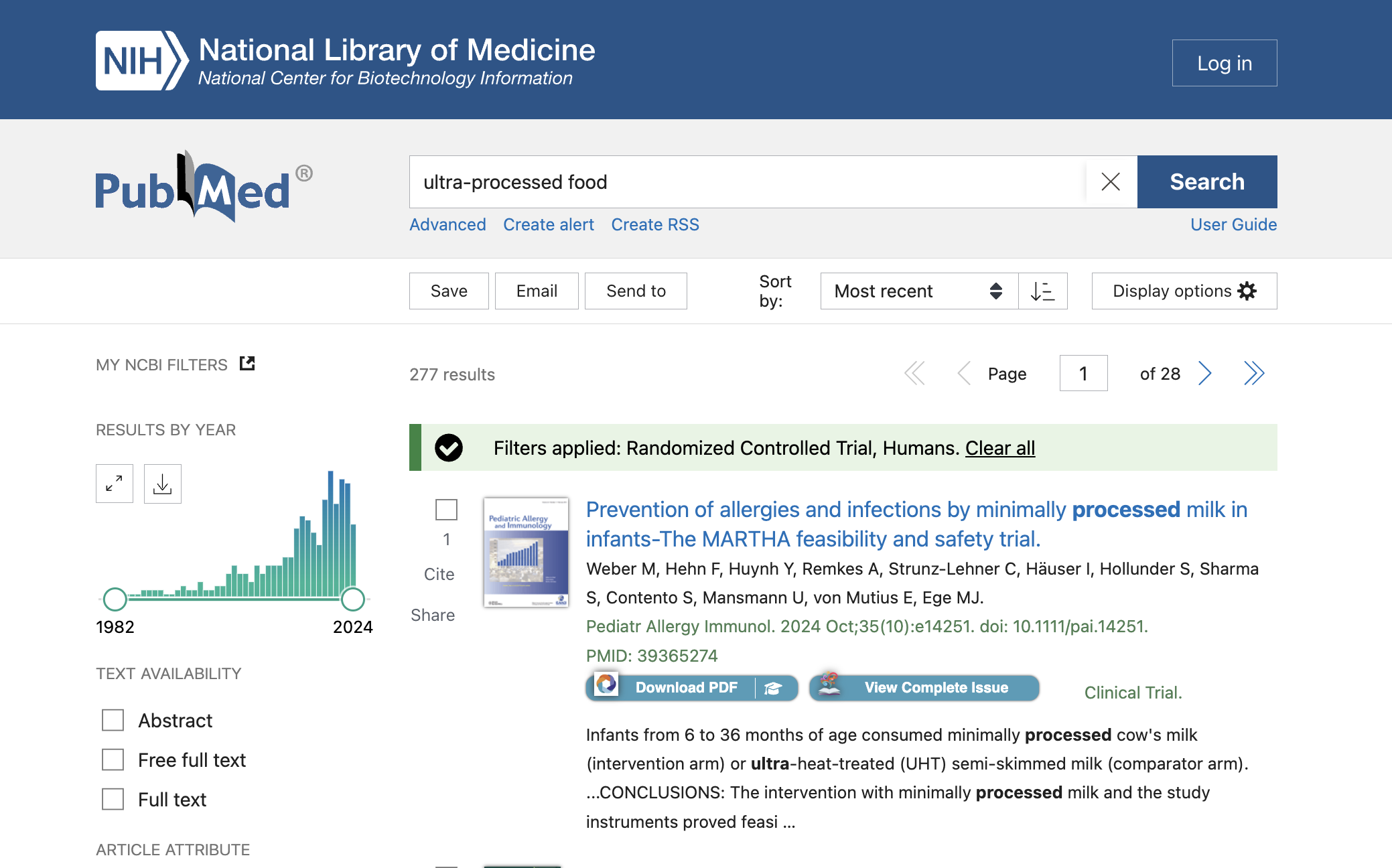

A PubMed search for "ultra-processed food" revealed 277 results when filtered for human participants and randomized controlled trials. However, not all of these results discuss ultra-processed foods specifically, so his statement that there are "hundreds and hundreds" of extensive studies on ultra-processed foods seems to be exaggerated.

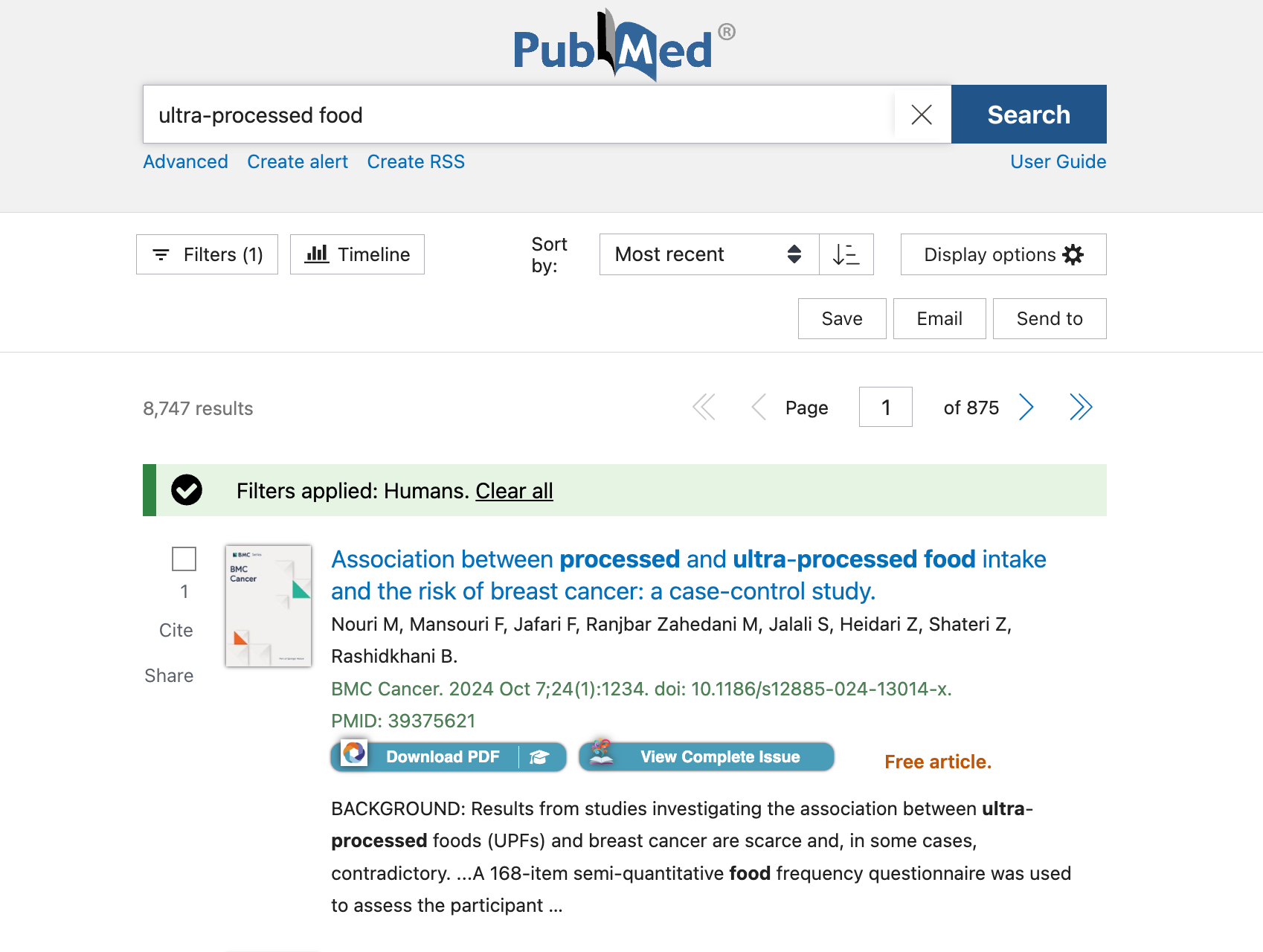

If the search only filters for humans (which will now include plenty of articles that can't be used to determine evidence and outcomes), there are 8,747 results.

That might be closer to what Hyman was referring to, although the statement was still incorrect since most of the results in this search can't tell us anything about how ultra-processed foods impact human health.

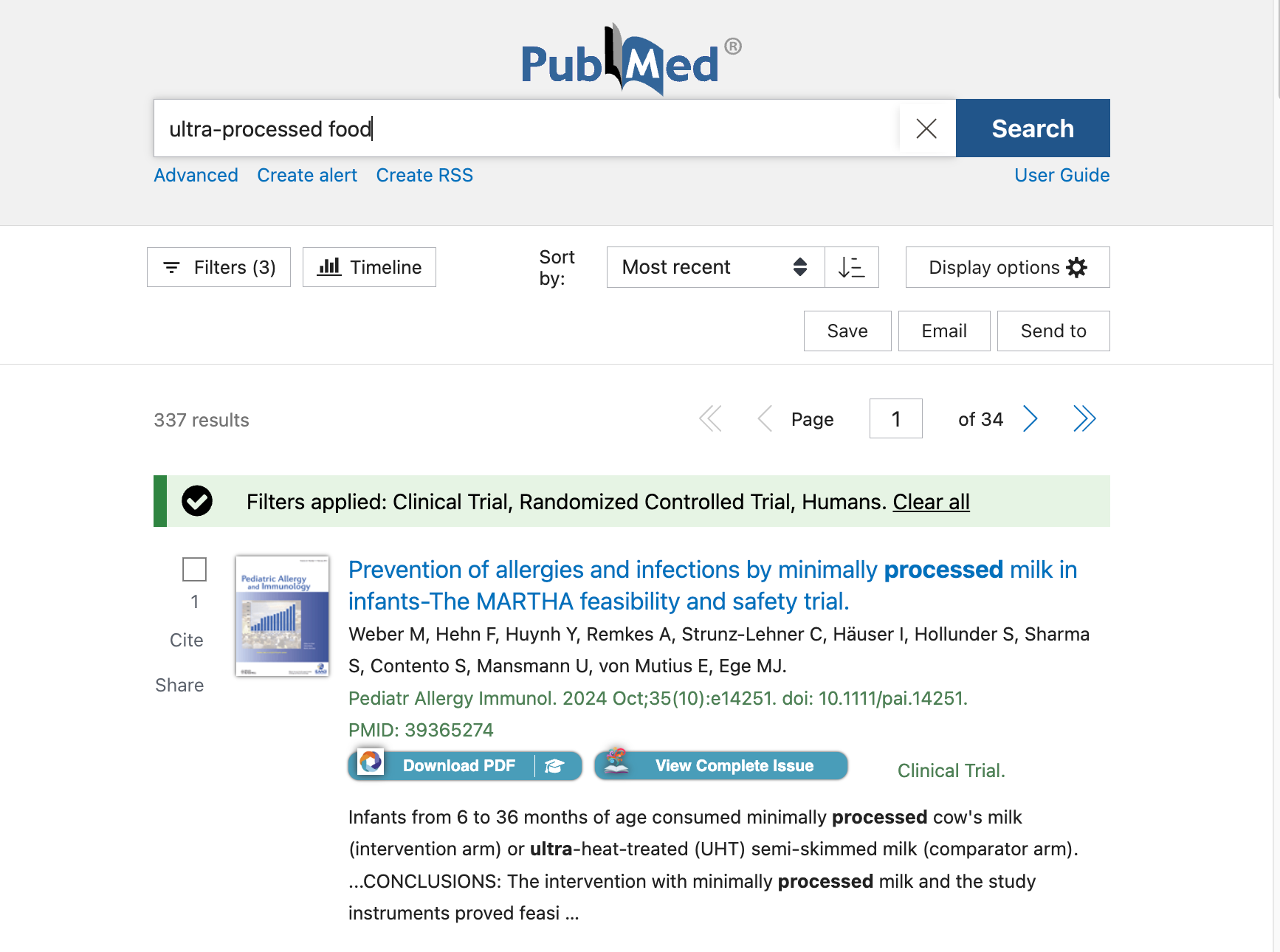

If all controlled trials and clinical studies (with humans) are included, at most, there are 337 PubMed results. Again, not all of these will be about ultra-processed food's effects on human health.

Back to the Ultra-Processed Outrage

Hyman's reel misrepresented at least a few details about Wilson's experiment and her credentials. He referred to her as "a nutritionist," a term that isn’t regulated, and seemed to suggest that Wilson was unqualified to assess food, diets, or nutrition.

He mentioned more than once that eating ultra-processed foods like this isn't representative of how people eat them in real life and seemed to appear most incensed that the article said "this is okay." However, Wilson's experiment was not a clinical trial to determine if ultra-processed foods were "okay."

Wilson did not argue that ultra-processed are the ultimate in nutrition. She made the case that a majority of Americans consume ultra-processed foods regularly, and that it is possible to do so while still meeting nutritional needs and not sabotaging health. Ultra-processed is not synonymous with a diet that only consists of candy, ice cream, and chips, even though that's how the media often presents it. Context matters, although it appears as if Hyman was not interested in the nuanced take that the article or Wilson's experiment represented.

Bought Off By Industry?

Hyman said that the Time article's author seemed to agree with Wilson's perspective that people who consume ultra-processed foods should not be shamed.

Shame is not a helpful tool to force positive health change. This is not a trauma-informed perspective.

Then Hyman said, "And by the way, this is exactly the talking points of the food industry... they basically hire and fund nutritionists. Forty percent of the information you're getting from registered dietitians on social media is coming from paid nutritionists who are paid by the food industry."

To avoid addressing a specific point, Hyman sidestepped the issue that Wilson's experiment highlighted and instead, attempted to undermine her credibility with the implication that she's been bought off by the food industry.

According to Wilson's website, she works for a healthcare nonprofit that provides care for marginalized and underserved people (and never requires payment from those who can’t afford it). There are no "Big Food" disclosures.

It seems to have been drawn from an NPR podcast2 that discussed a joint journalistic investigation between The Washington Post and The Examination. While journalistic investigations can provide important information, this does not mean that this is a true reflection of the entirety of the field of nutrition and dietetics. Study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and how the statistical analysis was done could all sway the type of numbers that come out of the analysis.

With those limitations in mind, this investigation analyzed more than 6,000 social media posts (not accounts, posts—it's not clear how many actual influencers were included) that were shared by dietitian influencers who had 10,000 or more followers.

Forty percent of "them," the podcast said (but it's not clear if "them" means 40% of the dietitians with larger followings or 40% of the total posts analyzed) used anti-diet language.

Of those who used anti-diet language, "a majority" shared sponsored content for food and beverage companies (and while General Mills and cereal was mentioned, it didn't detail what other types/brands were involved—making it possible that some of those sponsoring companies wouldn't be vilified in the same ultra-processed category as "sugary cereal.")

Bottom line: There's no evidence that 40% of all dietitians are bought off by the food industry.

Hyman's website doesn't have disclosures.3 He is, however, financially linked with numerous companies that profit from selling wellness-adjacent products and services.

👉 Cleveland Clinic4

👉 Function Health5

👉 Institute for Functional Medicine6

👉 Supplement sales on website7

👉 The Doctor’s Farmacy podcast8

👉 Book royalties9

👉 Levels10

👉 DNA Life11

There's nothing wrong with making money, but writing off someone for being "bought off" by Big Food (an industry with a revenue of about $985 billion) sidesteps that Hyman is one of the biggest names in the $5.6 trillion wellness industry. No, that doesn't mean he's a trillionaire or even that he controls the lion's share, but pointing at Big Food is a distraction from considering the financial influence of Big Wellness.

Wilson responded to Hyman's Instagram reel with an invitation to have a real conversation on either her podcast or his. As of the publication date for this post, Hyman does not appear to have accepted Wilson's offer.

What's "Really" Behind Ultra-Processed Foods and Bad Health Outcomes?

There's no formal definition of what, explicitly, ultra-processed means. Most seem to default to a particular food classification system (the NOVA), but it has plenty of flaws that make it impossible for the everyday person to know whether they're eating an unprocessed food (homemade soup) or an ultra-processed food (homemade soup that used a bouillon cube).

Observational studies12 have linked higher intake of processed foods with worse health outcomes over time. But is it the ultra-processing or something else?

I combed through dozens of recent news stories about the ultra-processed outrage, hoping to find some nuance. What I found was mostly the same recycled pearl-clutching, narrow-perspective arguments.

One article seemed to be heading there: Tamar Haspel's food column in The Washington Post.13 However, when it came down to it, her assessment was that weight gain caused by the offending foods was the real culprit behind the worse health outcomes.

American culture is at least unified in that something is linked with all these bad outcomes and that something appears to be worsening.

But what it is—and who should be blamed—is up for grabs.

The Blame Game

The recent ultra-processed drama primarily targets Big Food for its ultra-processing, ultra-calories, ultra-sugar, and ultra-salt. They caused the problem by creating cheap, tasty food that gets people "addicted." Bad, Big Food, bad.

Depending on who you listen to, individuals should be shamed and blamed. They ought to have more "self-control" or "willpower." They should be "less lazy" or "exercise more." They should "prioritize their health" and "think beyond the candy bar." Bad person, bad.

Despite the headlines that get the most circulation, researchers know that higher body weight isn't caused by laziness and that the problem isn't singular. Obesity remains tied to a narrative of “laziness”—even though this has been disproven (emphasis mine):

"Individuals with obesity face not only increased risk of serious medical complications but also a pervasive, resilient form of social stigma. Often perceived (without evidence) as lazy, gluttonous, lacking will power and self-discipline, individuals with overweight or obesity are vulnerable to stigma and discrimination in the workplace, education, healthcare settings, and society in general. Weight stigma can cause considerable harm to affected individuals, including physical and psychological consequences.

The damaging impact of weight stigma, however, extends beyond harm to individuals. The prevailing view that obesity is a choice and that it can be entirely reversed by voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more can exert negative influences on public health policies, access to treatments, and research."

If you scroll posts or read articles from the health, nutrition, and wellness world, you'll mostly see chatter about ultra-processed ingredients and body weight that blames Big Food, Big Pharma, laziness, addiction, and/or a lack of self-control.

These overly simplistic conclusions seem to make sense from the outside. People internalize the messaging. The system of blame, shame, and laziness becomes self-perpetuating.

Aren't We Forgetting Something?

Instead of curiosity and consideration to think outside the box—to ask what else might be going on—public health and people succumb to oversimplification.

Just like statistical analysis that neglects essential confounding variables, blaming Big Food and poor personal choices ignores the erosive impact of stress, trauma, and survival mode that has been the constant reality for generations of American people.

Those who vehemently oppose ultra-processed foods may talk like they understand the burden faced by Americans living with food insecurity, trauma, chronic conditions, poverty, homelessness, discrimination, and more, but awareness of what the social determinants of health are does not equate to empathy or understanding of how it feels to live under their effects.

Plenty will blame Big Food for "taking advantage" of poor people. How dare you make tasty, affordable junk that's causing these people's disease.

But this argument ignores the reality that poverty is a policy-preventable state. It is not the product of (yet more) laziness. When extra social support was provided in response to the pandemic, the poverty rate dropped to a record low. As those programs began to expire, poverty went up by the most significant increase on record (since 1967).

People may argue against government social support, but it's not a political issue in this context. If someone blames Big Food (because the government subsidizes the industry) and Big Pharma (same reason) for causing the "epidemic," it makes no sense to then put the onus of repair on individuals. Big Government should fix the Big Problems. But, interestingly, the people who blame Big don't lobby the government for sweeping, generous social support to offset the social determinants of health. Likewise, it makes no sense for wellness influencers to demand strict regulation for Big Food but lobby against scrutiny or oversight for Big Supplement.

It's almost as if everyone's working for Big Agenda instead of individual people.

Even Chris van Tulleken, the author of Ultra-Processed People, has stated that he doesn't believe that individuals are responsible for addressing the impacts of ultra-processed food. He called it a social justice issue, and said that if poverty were eliminated, so also would many health conditions linked with ultra-processed foods.14

What Aren't They Considering?

Scientists and researchers haven't even definitively agreed on what ultra-processed food is.

If you look at the large amounts of data analyzed in observational studies that are used to create associations (but not cause-and-effects) between things, you should also ask what other associations aren't being considered.

If chronic disease has gone up alongside the intake of ultra-processed foods, but we have not proven cause and effect, we must ask: What else has gone up?

- Income inequality and the wealth gap

- Inflation

- Healthcare costs

- Housing costs

- Medication costs

- Food costs

- Mass shootings and gun violence

- Stress and trauma

- Cost of higher education (and student debt)

- Deaths and complications from opioid use

- Distrust in experts across nearly every health, science, and medical field

- Childcare costs

That's a far from complete list. But clearly, we could make the case that as any of those have increased, so also have chronic health challenges. Statistics and data can be used to imply lots of things. But it's not an illogical leap to imagine that one or any of those elevations could also erode physical well-being.

Now, what about inverse associations, where chronic disease and ultra-processed food intake have gone up, but other things that might be related have gone down? Things like:

- Healthcare access

- Comprehensive insurance coverage

- Job security

- Wage stability

- Access to safe outdoor spaces

- Access to childcare

- Access to reproductive care

Again, not a complete list. But consider: For every alarmist headline and declarative statement about this or that causing disease, numerous things have not actually been ruled out.

Human health is complex. There will never be definitive answers for most health-related anything because:

- The food you procure

- is based on accessibility (financial, physical, mobility, etc.)

- and goes into a body

- with digestive and metabolic individualities

- influenced by specific external environments

- that respond to unique stressors, stigma, and trauma

- intertwined with systemic influences of society

- undermined by petty bickering and ideological values

- at the highest levels of every institution and organization

It is never entirely about someone and their "lifestyle choices."

This does not mean nothing matters. It doesn't mean all efforts are futile. It doesn't mean there's no hope.

But it can't be reduced to individual fault, blame, or shame. It is systemic, not singular.

References

- https://time.com/7007857/ultra-processed-foods-advocate/

- https://www.npr.org/2024/04/10/1243989381/how-big-food-co-opted-the-anti-diet-movement-for-profit

- drhyman.com/

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/ staff/19048-mark-hyman

- functionhealth.com/

- ifm. org/about/profile/mark-hyman

- drhyman .com/collections/shop-all

- https://variety.com/2024/biz/news/dr-mark-hyman-wme-1236041934/

- https://www.simonandschuster.com/ authors/Mark-Hyman/1125472

- levels. com/blog/dr-mark-hyman-joins-levels-as-advisor

- markhyman .dnalifevms.com/default.aspx

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667193X24001868

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/food/2024/09/20/ultra-processed-foods-obesity-reasons-overeating/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dzUDhstqXbg